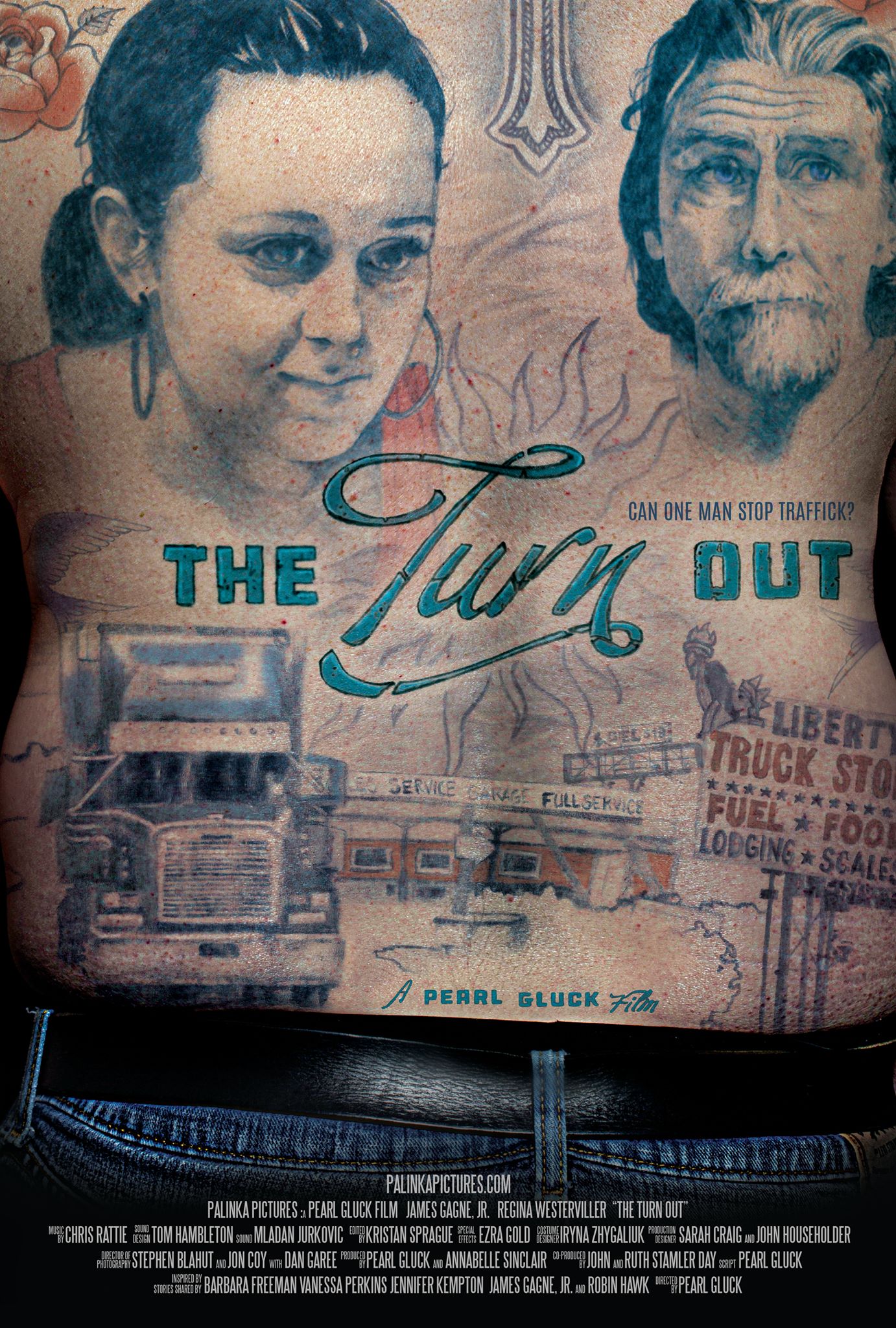

THE TURN OUT

Synopsis

In a small town in Southern Appalachia, a trucker must decide if he will stand up and take action against sex trafficking at his truckstop. The Turn Out melds the testimony and talents of sex trafficking survivors, anti-trafficking activists, and truckers with the work of film professionals to create an unflinching docu-drama of moral dilemma and personal connection in the local landscape of Glouster, Ohio, Athens County, and Mineral Wells, West Virginia.

“My grandmother was sold at a local truckstop from the time she was 12 until she turned 18 and became an adult … your movie hit me hard. It was as if I was watching my grandmother on that screen.”

– Jessica Graham, Survivor’s Ink

“I’m still thinking about the amazing performances you got from your actors.”

– Tony Buba, Braddock Films

Director’s Statement

In 2014, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received reports of 3,598 sex trafficking cases in the United States alone. The year before that, on September 2013, two arrests were made in Athens, Ohio, in a domestic sex trafficking case: a young girl was being trafficked by her father’s girlfriend in exchange for drugs and money. Eleven years prior, in 2002, a trucker parked at a travel center in Detroit made a phone call to report his suspicions of two girls being trafficked at his truckstop. He saved the lives of a young girl and her cousin who were kidnapped from Toledo, Ohio, and trafficked across state lines.

Based initially on these two stories and the research I conducted in Ohio when I was teaching at Ohio University’s School of Film, I wrote The Turn Out in 2014.

Set in Southern Appalachia, the film examines domestic trafficking at truckstops in rural America through the story of a trucker named Crowbar who comes to the excruciating realization that he has become an active part of a sex trafficking ring when he engages with an underage victim. The film explores the choices he makes once he is aware of her situation.

While The Turn Out is inspired by the story of a trucker who did not purchase sex but made a phone call at a truckstop that saved the lives of two victims, the fictionalized version the trucker is a less-than-heroic everyman who actually engages in the sex trade. To him, a quick, inexpensive rendezvous with a prostitute is an innocuous respite. The Turn Out challenges simplistic understandings of bystander, perpetrator, and victim. By the end of the film, Crowbar comes to realize that he is, in fact, culpable and could play an essential role in prevention.

To inform the narrative, I interviewed survivors of trafficking, truckers, and legislators and incorporated their voices into the narrative. The documentary elements of the film also informed the casting. For example, a trucker for the United States Post Office plays Crowbar, a survivor of 25 years of being trafficked on the streets of Columbus, Ohio, is the advocate who works with the underage victim. Neveah (“Heaven spelled backwards”) is played by a young woman who, herself, was subjected to inner-family trafficking because of drug addiction in Chauncey, one of the five poorest counties in Ohio. She shared her own story about how she had managed to escape her heroine-addicted mother when she was traded for drugs to a dealer. Jack Wright, co-founder of Appalshop (Appalachia’s multimedia arts center), tells the story of the Wipple Company Store in Fayette county on early signs of trafficking in the region.

Staying true to the regionality of the issue, the film is set at the aging Liberty Truck Stop in West Virginia, and Glouster, also one of the poorest counties in Southern Ohio.

As an additional note on the storytelling, my grandmother, a survivor of Auschwitz, often said to me: “I don’t know why they keep making those films on the Holocaust, killing us over and over on screen.” I took her sentiments to heart and for this reason, I decided not to show the actual sexual abuse in The Turn Out on screen. The film focuses on a bystander who can challenge our proverbial blindness and encourage the viewers to see what is otherwise hidden but directly on our doorsteps.

This film raises questions of women’s agency and victimization and counters the misconception that trafficking predominantly involves girls and women who come from outside the United States. This film highlights that a majority of the women committing a “crime” of solicitation are actually forced into it. For example, State Representative Teresa Fedor, a consultant on the film, has made this her bipartisan life work and after a long struggle, finally passed the End Demand Act in Ohio in June 2014.

From my research, it is clear that addiction, poverty, and lack of opportunities are some of the leading causes of domestic inner-family sex trafficking.