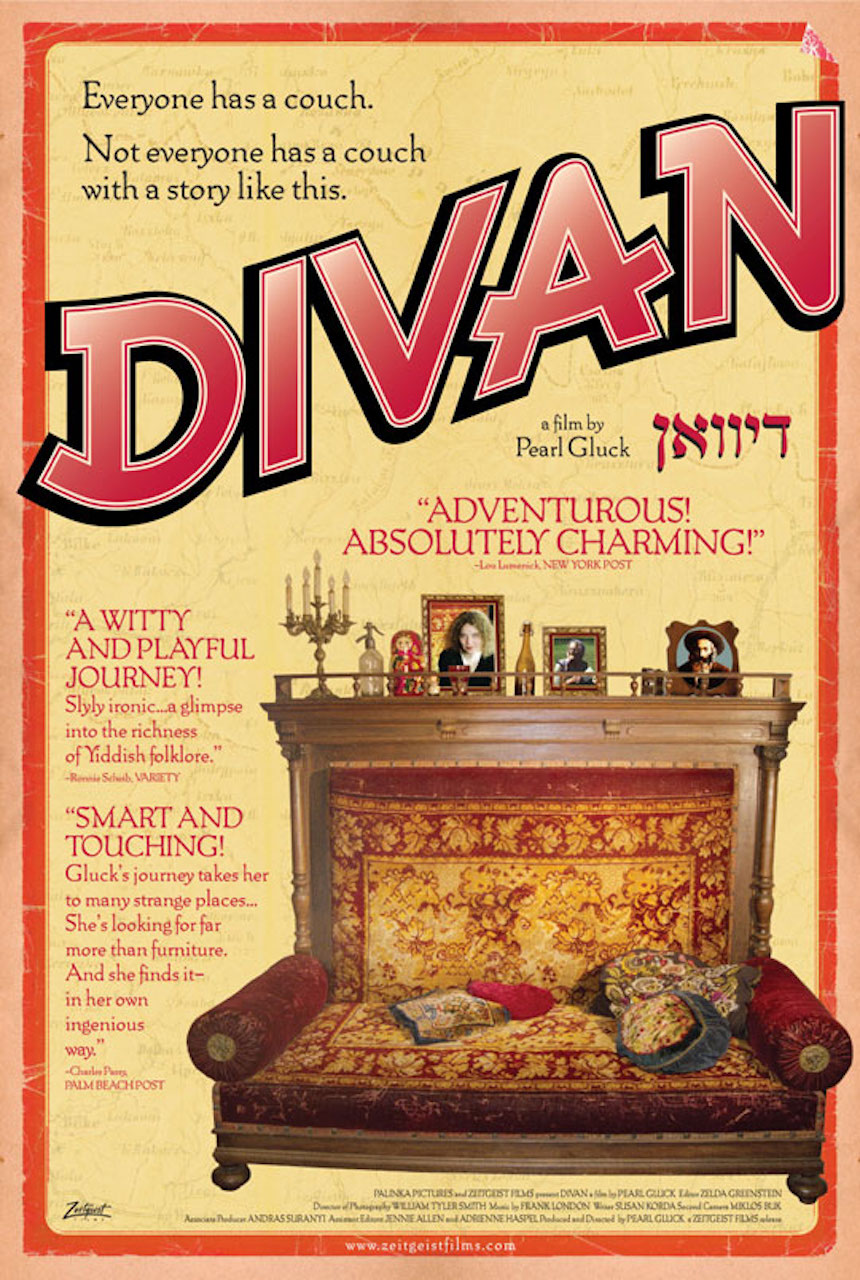

DIVAN

To reclaim an ancestral couch upon which esteemed rabbis slept, Pearl Gluck travels from her Hasidic community in Brooklyn to her roots in Hungary. Along the way, a colorful cast of characters gets involved – the couch exporter, her ex-communist cousin in Budapest, a pair of matchmakers, and a renegade group of formerly ultra-orthodox Jews. Divan is a visual parable that offers the possibility of personal reinvention and cultural re-upholstery.

Director’s Statement

It was my father who gave me my first video camera in 1996 as a gift for my trip to Hungary on a Fulbright grant. Five years later we end up in an editing room together viewing footage for Divan, a film he does not approve of and does not want to participate in. And yet, Divan is at its heart a father/daughter tale – he, the unwilling protagonist, which makes me the unwilling antagonist.

In some ways, it should come as no surprise that I took up film to tell stories. The camera was always a presence in my family history, my father behind the super 8, a silent witness to both dissolution of a family and also its ultimate realignment. But, where I come from, it’s not part of the norm to watch movies, let alone create them, because it is considered a diversion from a life of piety, devotion, and modesty. Hence, the paradox of my cinematic project: on the one hand, film has informed my entire life, on the other hand, it was entirely forbidden.

Indeed it was in Hungary while conducting oral histories that my Hasidic past began to haunt me. The ruptured trajectory of my own family kept returning. In awe of the ruins of the Hungarian Jewish landscape, I was forced to confront my act of leaving the Hasidic community of my youth. Ever an ethnographer, I turned the camera inward. When I finally got to my great great grandfather’s house and saw the famous couch upon which the Kossony rebbe slept, I saw the medium for understanding my own complex relationship with my Hasidic legacy. The couch became a magical homage to the rebbes, a sacred memory object, and a concrete tool for a personal and communal cultural archeology. It gave me the possibility of yearning, contemplating, and reflecting on the world I left behind.

While grappling with this loaded legacy, I met other people who also left the Hasidic and ultra-Orthodox world. Their voices form a chorus, that takes this film out of the realm of the strictly autobiographical and into a larger communal narrative. By interweaving the elements of my personal story with the chorus as well as the physicality of the couch itself, I sought to create a three-layered tapestry of a postmodern Hasidic tale, embracing the elements of mystery, devotion, and joy. After a long journey across the Atlantic, the divan emerges from its crate, and posits no easy resolution. Instead, I see it offering the possibility of culturally re-upholstering the framework of “home vs. exile” with the richly textured fabric of engagement.